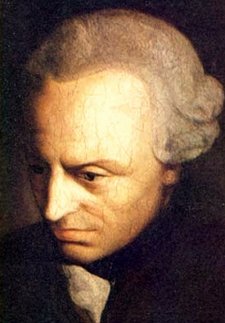

Immanuel Kant famously believed that “the problem of organizing a state, however hard it may seem, can be solved even for a race of devils, if only they are intelligent.” These rational devils will realize that they need well designed and enforced laws for their own self-preservation, even though each “is secretly inclined to exempt himself from them.” So they need “to establish a constitution in such a way that, although their private intentions conflict, they check each other, with the result that their public conduct is the same as if they had no such evil intentions.”

Immanuel Kant famously believed that “the problem of organizing a state, however hard it may seem, can be solved even for a race of devils, if only they are intelligent.” These rational devils will realize that they need well designed and enforced laws for their own self-preservation, even though each “is secretly inclined to exempt himself from them.” So they need “to establish a constitution in such a way that, although their private intentions conflict, they check each other, with the result that their public conduct is the same as if they had no such evil intentions.”

In short, in this essay Perpetual Peace, published about 30 years after Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, Kant was optimistic that with a well designed constitution, something like an Invisible Hand (and sometimes, surely, a visible foot) could turn opportunistic political behavior into responsible, statesmanlike, governance.

Of course, this is all probably irrelevant for those following the current election cycle in the US. Kant thought that cleverly designed rules for the game could handle greed. But all bets are off if either the devils running for office, or those whose votes they are courting, lack intelligence, understanding, or rationality. So, well, all bets are off then.

A time-traveling Kant would nonetheless be intrigued by the political biography of the Senate majority leader, Mitch McConnell. At least, if the account developed by Alec MacGillis, author of The Cynic: The Political Education of Mitch McConnell, tracks the truth. In his recent attempt in The New York Times to explain McConnell’s tactics for the game of selecting and approving the appointment of a new justice to the Supreme Court, MacGillis portrays the Senate majority leader as exactly the kind of intelligent devil Kant had in mind.

The best way to understand Addison Mitchell McConnell Jr. has been to recognize that he is not a conservative ideologue, but rather the epitome of the permanent campaign of Washington: What matters most isn’t so much what you do in office, but if you can win again.

As an aspiring young Republican — first, a Senate and Ford administration staff member and then county executive in Louisville — Mr. McConnell leaned to the moderate wing of his party on abortion rights, civil rights and many other issues. It was only when he ran for statewide office, for the Senate in 1984, that he began to really tack right. Mr. McConnell won by a razor-thin margin in a year when Ronald Reagan handily won Kentucky. The lesson was clear: He needed to move closer to Reagan, which he promptly did upon arriving in Washington.

From that point on, the priority was winning every six years and, once he’d made his way up the ranks of leadership, holding a Republican majority. In 1996, that meant voting for a minimum-wage increase to defuse a potential Democratic talking point in his re-election campaign. In 2006, as George W. Bush wrote in his memoir, it meant asking the president if he could start withdrawing troops from Iraq to improve the Republicans’ chance of keeping the Senate that fall, when Mr. McConnell was set to become its leader.

A year later, it meant ducking out of the intense debate on the Senate floor about immigration reform to avoid making himself vulnerable on the issue. It is no accident that the legislative issue Mr. McConnell has become most identified with, weakening campaign finance regulations, is one that pertains directly to elections.

This is also the best way to understand Mr. McConnell’s staunch opposition to the president: It is less about blocking liberal policy goals than about boosting Republican chances.

MacGillis concedes that McConnell’s tactical obstructionism has been successful on its own terms:

The resistance from Mr. McConnell has had an enormous influence on the shape of Obama’s presidency. It has limited the president’s accomplishments and denied him the mantle of the postpartisan unifier he sought back in 2008.

But the game isn’t over yet, and McGillis wonders whether McConnell has overplayed his hand in the aftermath of Justice Antonin Scalia’s death.

This blog does not really have a dog in that fight. We’re interested more in the concepts and categories we use to think through issues than we are (at least within this blog) in the political conclusions they lead to. My interest in McGillis’s portrait of McConnell is about the viability of Kant’s constitutional optimism. Some deliberately adversarial institutions — like Wimbledon tennis matches, courtroom law, markets without dangerously exploitable market failures — can licence the players to pursue their own interests in a contest with well designed rules and close monitoring for compliance. In these cases those outside “the game” will benefit even if the “players” care only about their own interests.

But can we possibly expect a modern democracy to work well, and justly, if the players vying for, and holding, office are all rational devils? Do the US Constitution and other defining features of the political infrastructure (such as the Federal Election Commission and the 50 different states’ laws for drawing up federal constituencies and voter-eligibility rules) constitute the kinds of rules that will, as Kant put it, convert selfish or evil private intentions into virtuous public conduct?

Even Mitch McConnell (thought not perhaps Francis Underwood) would surely agree that the answer to these questions is No. When this blog ponders politics, it will generally be to explore “why not?” or “where, then, from here?”