(Posted by Wayne.)

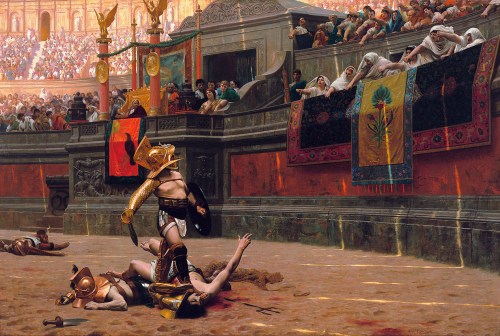

… and if so, is what goes on there like hockey or figure skating?

We standardly think of the adversarial legal system as one of the “classic” deliberately adversarial institutions. (This blog is about whether there are special rules for the design of, and behavior within, such institutions.) The most visible — and tele-visual — parts of the system involve lawyers representing two or more sides of a case battling it out, within the rules, to advance the interests of their clients (or of The People, in the case of prosecutors).

But not all parts of the justice or legal system are adversarial. It’s an open question how we should think about both the theory and the practice of what goes on at the “top” of the system — the Supreme Court (to give a US example; but all constitutional democracies have something similar). It certainly looks adversarial in important ways. Its role is to settle contentious issues in the law, and it does this by dealing with actual cases where one side doggedly disagrees with the other. Like lower courts, it will also listen to lawyers representing the opposing sides. And of course, we can’t ignore the fact that the justices on the Court are nominated by the President and approved (or rejected) by a very adversarial legislature.

And yet, the work of the justices themselves is expected to be entirely professional. They are meant to figure out, individually and collectively, the best interpretation of laws and the Constitution. They are not supposed to be representing any particular interest, and are even expected to set aside their own biases and interests — and if they cannot, on a particular case, to step aside. No individual member of the Court is supposed to be trying to “win” anything. Cases are supposed to be decided on their merits alone — may the best arguments be the winners.

Next week the Court will begin its deliberations on the Affordable Care Act. In advance of the three sessions where the justices will hear arguments, the New York Times has recently highlighted two interesting aspects of the nature of the Court within the deliberately adversarial justice system.

First, it noted that

The White House has begun an aggressive campaign to use approaching Supreme Court arguments on the new health care law as a moment to build support for the measure seen as President Obama’s signature legislative achievement, hoping to shape public opinion on an issue at the center of the battle for the White House and Congress.

Now this would not be unusual as a matter of politics: the President and his party are part of another nakedly adversarial system called democratic politics, and elections are looming. But what is unusual about these current plans is that they suggest that such politics may also be trying to influence the justices themselves.

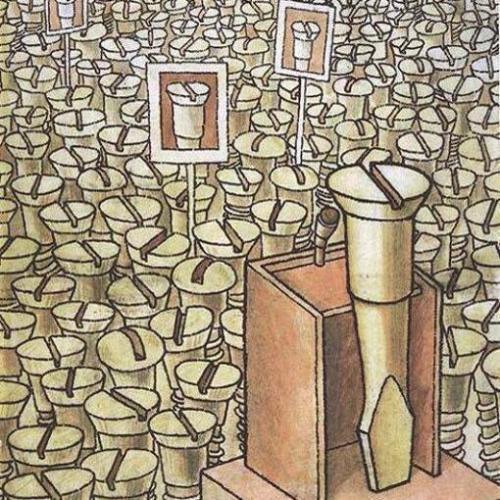

The advocates and officials mapped out a strategy to call attention to tangible benefits of the law, like increased insurance coverage for young adults. Sensitive to the idea that they were encouraging demonstrations, White House officials denied that they were trying to gin up support by encouraging rallies outside the Supreme Court, just a stone’s throw from Congress on Capitol Hill…

Supporters of the law plan to hold events outside the court on each day of oral argument. The events include speeches by people with medical problems who have benefited or could benefit from the law. In addition, supporters will arrange for radio hosts to interview health care advocates at a “radio row,” at the United Methodist Building on Capitol Hill.

The law’s supporters may have to get there early if they want the best patch of sidewalk:

Opponents of the law will be active as well and are planning to show their sentiments at a rally on the Capitol grounds on March 27, the second day of Supreme Court arguments. Republican lawmakers, including Senator Patrick J. Toomey of Pennsylvania and Representative Michele Bachmann of Minnesota, are expected to address the rally, being organized by Americans for Prosperity, with support from conservative and free-market groups like the Tea Party Express.

Your guess is as good as mine about what influence all of this will have on the nine individuals charged with the final decision. It is nonetheless a curious “grey area” partisan political activity swirling around a part of the justice system that is supposed to be non-partisan and non-political — or at the very least, not susceptible to the emotional volume of support for one side or the other. The White House’s own cautious framing of their strategy seems to acknowledge that they are toeing close to a line they don’t want to cross.

Meanwhile, we hear whispers that the Chief Justice himself, John Roberts, may be approaching his pending vote among his colleagues with concerns that go beyond the correct interpretation of the law. The guess is that he will not necessarily vote for the side with the best arguments.

The consensus among scholars and Supreme Court practitioners is that Chief Justice Roberts is unlikely to add the fifth vote to those of the four justices in the court’s liberal wing to uphold the law. But he is said to be quite likely to provide a sixth vote should one of the other more conservative justices decide to join the court’s four more liberal members.

Why might he be willing to vote either way?

The case will require the chief justice to choose between two competing instincts.

On the one hand, he views himself as a steward of the court’s prestige and authority, and he has called for incremental decisions from large majorities rather than broad but sharply divided rulings. “As chief justice, Roberts has been extremely careful with the institutional reputation of the court,” said Barry Friedman, a law professor at New York University who has filed a brief urging the court to uphold the law.

The court has not rejected legislation as ambitious as the health care law since the 1930s. There is, moreover, only one plausible way for the justices to strike down the law, scholars who study the court say: by a 5-to-4 vote divided along ideological lines.

All of that might augur a cautious approach.

Now this is not unusual practice for judges in constitutional courts: to decide politically charged cases in ways that will serve to uphold the legitimacy of the Court — where legitimacy requires its being perceived as a fair, neutral party.

So what might this tell us about principles for design and professional behavior in other deliberately adversarial institutions? Sometimes “players” have to act in ways that uphold the “integrity of the game” even if this requires refraining from a winning tactic, or from carrying out a routine professional duty.

Interestingly enough, in the controversial Citizens United ruling, the Roberts Court struck down legislation that the politicians had put in place to preserve (some of) the integrity of their adversarial institution. The politicians had agreed to limit the influence of corporate money, along with perceptions of bias and corruption. Not all members of the majority denied that a flood of corporate money would have these consequences for democratic processes, but they felt nevertheless that rights to free speech couldn’t be infringed for the sake of the legitimacy of that process. If the rumors are true now, however, it seems that the Chief Justice may be willing to overlook a fundamental right being infringed by the new health care law for the sake of the Court’s “prestige and authority.”

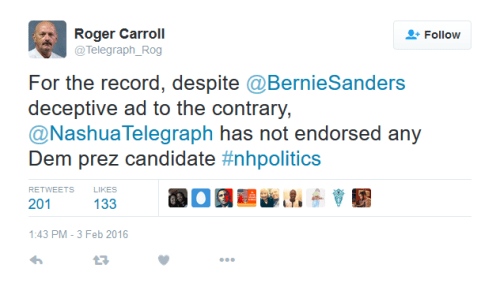

Carroll, the editor of the Nashua Telegraph, called Sanders’ ad “deceptive.”

Carroll, the editor of the Nashua Telegraph, called Sanders’ ad “deceptive.”

Immanuel Kant famously believed that “the problem of organizing a state, however hard it may seem, can be solved even for a race of devils, if only they are intelligent.” These rational devils will realize that they need well designed and enforced laws for their own self-preservation, even though each “is secretly inclined to exempt himself from them.” So they need “to establish a constitution in such a way that, although their private intentions conflict, they check each other, with the result that their public conduct is the same as if they had no such evil intentions.”

Immanuel Kant famously believed that “the problem of organizing a state, however hard it may seem, can be solved even for a race of devils, if only they are intelligent.” These rational devils will realize that they need well designed and enforced laws for their own self-preservation, even though each “is secretly inclined to exempt himself from them.” So they need “to establish a constitution in such a way that, although their private intentions conflict, they check each other, with the result that their public conduct is the same as if they had no such evil intentions.”

According to a

According to a

The scandal currently engulfing Football’s

The scandal currently engulfing Football’s